4 Cardinal Virtues

4.1 Introduction

The four Cardinal Virtues are Wisdom, Justice, Courage, and Temperance. Because data science is, ultimately, a moral act, we use these virtues to guide our work. Every data science project begins with a question.

Wisdom starts by creating the Preceptor Table. What data, if we had it, would allow us to answer our question easily? If the Preceptor Table has one outcome, then the model is predictive. If it has more than one (potential) outcome, then the model is causal. We then explore the data we have. You can never look too closely at your data. Key question: Are the data we have close enough to the data we want (i.e., the Preceptor Table) that we can consider both as coming from the same population? If not, we can’t proceed further. Key in making that decision is the assumption of validity. Do the columns in the Preceptor Table match the columns in the data?

Justice starts with the Population Table – the data we want to have (i.e., the Preceptor Table), the data which we actually have, and all the other data from that same population. Each row of the Population Table is defined by a unique Unit/Time combination. We explore three key issues about the Population Table. First, does the relationship among the variables demonstrate stability, meaning is the model stable across different time periods? Second, are the rows associated with the data and, separately, the rows associated with the Preceptor Table representative of all the units from the population? Third, for causal models only, we consider unconfoundedness.

Courage allows us to explore different models. Justice gave us the Population Table. Courage creates the data generating mechanism. We begin with the basic mathematical structure of the model. With that structure in mind, we decide which variables to include. We estimate the values of the unknown parameters. We avoid hypothesis tests. We check our models for consistency with the data we have. We select one model.

Temperance guides us in the use of the model we have created to answer the questions with which we began. We create posteriors of quantities of interest. We should be modest in the claims we make. Humility is important. The posteriors we create are never the “truth.” The assumptions we made to create the model are never perfect. Yet decisions made with flawed posteriors are almost always better than decisions made without them.

4.2 Wisdom

Wisdom requires the creation of a Preceptor Table, some exploratory data analysis, and a determination, using the concept of validity, as to whether or not we can (reasonably!) assume that the two come from the same population.

Wisdom helps us decide if we can even hope to answer our question with the data that we have.

A Preceptor Table is smallest possible table with rows and columns such that, if there is no missing data, our question is easy to answer.

One key aspect of this Preceptor Table is whether or not we need more than one potential outcome in order to calculate our estimand. For example, if we want to know the causal effect of exposure to Spanish-speakers on attitude toward immigration then we need a causal model, one which estimates that attitude for each person under both treatment and control. The Preceptor Table would require two columns for the outcome. If, on the other hand, we only want to predict someone’s attitude, or compare one person’s attitude to another person’s, then we would only need a Preceptor Table with one column for the outcome.

Every model is predictive, in the sense that, if we give you new data — and it is drawn from the same population — then you can create a predictive forecast. But only a subset of those models are causal, meaning that, for a given individual, you can change the value of one input and figure out what the new output would be and then, from that, calculate the causal effect by looking at the difference between two potential outcomes.

With prediction, all we care about is forecasting \(Y\) given \(X\) on some as-yet-unseen data. But there is no notion of “manipulation” in such models. We don’t pretend that, for Joe, we could turn variable \(X\) from a value of \(5\) to a value of \(6\) by just turning some knob and, by doing so, cause Joe’s value of \(Y\) to change from \(17\) to \(23\). We can compare two people (or two groups of people), one with \(X\) equal to \(5\) and one with \(X\) equal to \(6\), and see how they differ in \(Y\). The basic assumption of predictive models is that there is only one possible \(Y\) for Joe. There are not, by assumption, two possible values for \(Y\) for Joe, one if \(X\) equals \(5\) and another if \(X\) equals \(6\). The Preceptor Table has a single column under \(Y\) if that is all we need to answer the question.

With causal inference, however, we can consider the case of Joe with \(X = 5\) and Joe with \(X = 6\). The same mathematical model can be used. And both models can be used for prediction, for estimating what the value of \(Y\) will be for a yet-unseen observation with a specified value for \(X\). But, in this case, instead of only a single column in the Preceptor Table for \(Y\), we have at least two (and possibly many) such columns, one for each of the potential outcomes under consideration.

The difference between predictive models and causal models is that the former have one column for the outcome variable and the latter have more than one column.

Second, we look at the data we have and perform an exploratory data analysis, an EDA. You can never look at your data too much. The most important variable is the one we most want to understand/explain/predict. In the models we create in later chapters, this variable will go on the left-hand side of our mathematical equations. Some academic fields refer to this as the “dependent variable.” Others use terms like “response” or “outcome.” Whatever the terminology, we need to explore the distribution of this variable, its min/max/range, its mean and median, its standard deviation, and so on.

@roas write:

Most important is that the data you are analyzing should map to the research question you are trying to answer. This sounds obvious but is often overlooked or ignored because it can be inconvenient. Optimally, this means that the outcome measure should accurately reflect the phenomenon of interest, the model should include all relevant predictors, and the model should generalize to the cases to which it will be applied.

For example, with regard to the outcome variable, a model of incomes will not necessarily tell you about patterns of total assets. A model of test scores will not necessarily tell you about child intelligence or cognitive development. …

We care about other variables as well, especially those that are most correlated/connected with the outcome variable. The more time that we spend looking at these variables, the more likely we are to create a useful model.

Third, the (almost always imaginary) population is key. We need the data we want — the Preceptor Table — and the data we have to be similar enough that we can consider them as all having come from the same statistical population. From Wikipedia:

In statistics, a population is a set of similar items or events which is of interest for some question or experiment. A statistical population can be a group of existing objects (e.g. the set of all stars within the Milky Way galaxy) or a hypothetical and potentially infinite group of objects conceived as a generalization from experience (e.g. the set of all opening hands in all the poker games in Las Vegas tomorrow).

Mechanically, assuming that the Preceptor Table and the data are drawn from the same population is the same thing as “stacking” the two on top of each other. For that to make sense, the variables must mean the same thing — at least mostly — in both cases. This is the assumption of validity.

If we assume that the data we have is drawn from the same population as the data in the Preceptor Table is drawn from, then we can use information about the former to make inferences about the latter. We can combine the Preceptor Table and the data into a single Population Table. If we can’t do that, if we can’t assume that the two sources come from the same population, then we can’t use our data to answer our questions. The heart of Wisdom is knowing when to walk away. As John Tukey noted:

The combination of some data and an aching desire for an answer does not ensure that a reasonable answer can be extracted from a given body of data.

4.3 Justice

Justice concerns four topics: the Population Table, stability, representativeness, and unconfoundedness.

The Population Table includes a row for each unit/time combination in the underlying population from which both the Preceptor Table and the data are drawn. It can be constructed if the validity assumption is (mostly) true. It includes all the rows from the Preceptor Table. It also includes the rows from the data set. It usually has other rows as well, rows which represent unit/time combinations from other parts of the population.

There are three key issues to explore in any Population Table: stability, representativeness and unconfoundedness.

Stability means that the relationship between the columns in the Population Table is the same for three categories of rows: the data, the Preceptor Table, and the larger population from which both are drawn.

Never forget the temporal nature of almost all real data science problems. Our Preceptor Table will focus on rows for today or for the near future. The data we have will always be from before now. We must almost always assume that the future will be like the past in order to use data from the past to make predictions about the future.

Representativeness, or the lack thereof, concerns two relationship, among the rows in the Population Table. The first is between the Preceptor Table and the other rows. The second is between our data and the other rows. Ideally, we would like both the Preceptor Table and our data to be random samples from the population. Sadly, this is almost never the case.

Validity is about the columns in our Population Table. Stability and representativeness are about the rows.

Unconfoundedness means that the treatment assignment is independent of the potential outcomes, when we condition on pre-treatment covariates. This assumption is only relevant for causal models. We describe a model as “confounded” if this is not true. The easiest way to ensure unconfoundedness is to assign treatment randomly.

4.4 Courage

Courage begins with the exploration and testing of different models. It concludes with the creation of the Data Generating Mechanism.

Courage begins by a discussion of the functional form we will be using. This is usually straight-forward because it follows directly from the type of the outcome variable: continuous implies a linear model, binary implies logistic, and more than two categories suggests multinomial logistic. We provide the mathematical formula for this model, using y and x as variables. The rest of the discussion is broken up into three sections: “Models,” “Tests,” and “Data Generating Mechanism.”

Courage requires math.

The three languages of data science are words, math and code, and the most important of these is code.

We need to explain the structure of our model using all three languages, but we need Courage to implement the model in code.

Courage requires us to take the general mathematical formula and then make it specific. Which variables should we include in the model and which do we exclude? Every data science project involves the creation of several models, each with one or more unknown parameters.

Code allows us to “fit” a model by estimating the values of the unknown parameters. Sadly, we can never know the true values of these parameters. But, like all good statisticians, we can express our uncertain knowledge in the form of posterior probability distributions. With those distributions, we can compare the actual values of the outcome variable with the “fitted” or “predicted” results of the model. We can examine the “residuals,” the difference between the fitted and actual values.

A parameter is something which does not exist in the real world. (If it did, or could, then it would be data.) Instead, a parameter is a mental abstraction, a building block which we will use to to help us accomplish our true goal: To replace at least some of the questions marks in the actual Preceptor Table. Since parameters are mental abstractions, we will always be uncertain as to their value, however much data we might collect.

Randomness is intrinsic to this fallen world.

Null hypothesis testing is a mistake. There is only the data, the models and the summaries therefrom.

The final step of Courage is to select the final model, the Data Generating Mechanism.

4.5 Temperance

Temperance uses the Data Generating Mechanism to answer the specific question with which we began. Humility reminds us that this answer is always a lie. We can also explore the general question by using the DGM to calculate many similar quantities of interest, displaying the results graphically.

There are few more important concepts in statistics and data science than the Data Generating Mechanism. Our data — the data that we collect and see — has been generated by the complexity and confusion of the world. God’s own mechanism has brought His data to us. Our job is to build a model of that process, to create, on the computer, a mechanism which generates fake data consistent with the data which we see. With that DGM, we can answer any question which we might have. In particular, with the DGM, we provide predictions of data we have not seen and estimates of the uncertainty associated with those predictions. We can fill in the missing values in the Preceptor Table and then, easily, calculate all Quantities of Interest.

Justice gave us the Population Table. Courage created the DGM, the fitted model. Temperance will guide us in its use.

Having created (and checked) a model, we now use the model to answer questions. Models are made for use, not for beauty. The world confronts us. Make decisions we must. Our decisions will be better ones if we use high quality models to help make them.

Sadly, our models are never as good as we would like them to be. First, the world is intrinsically uncertain.

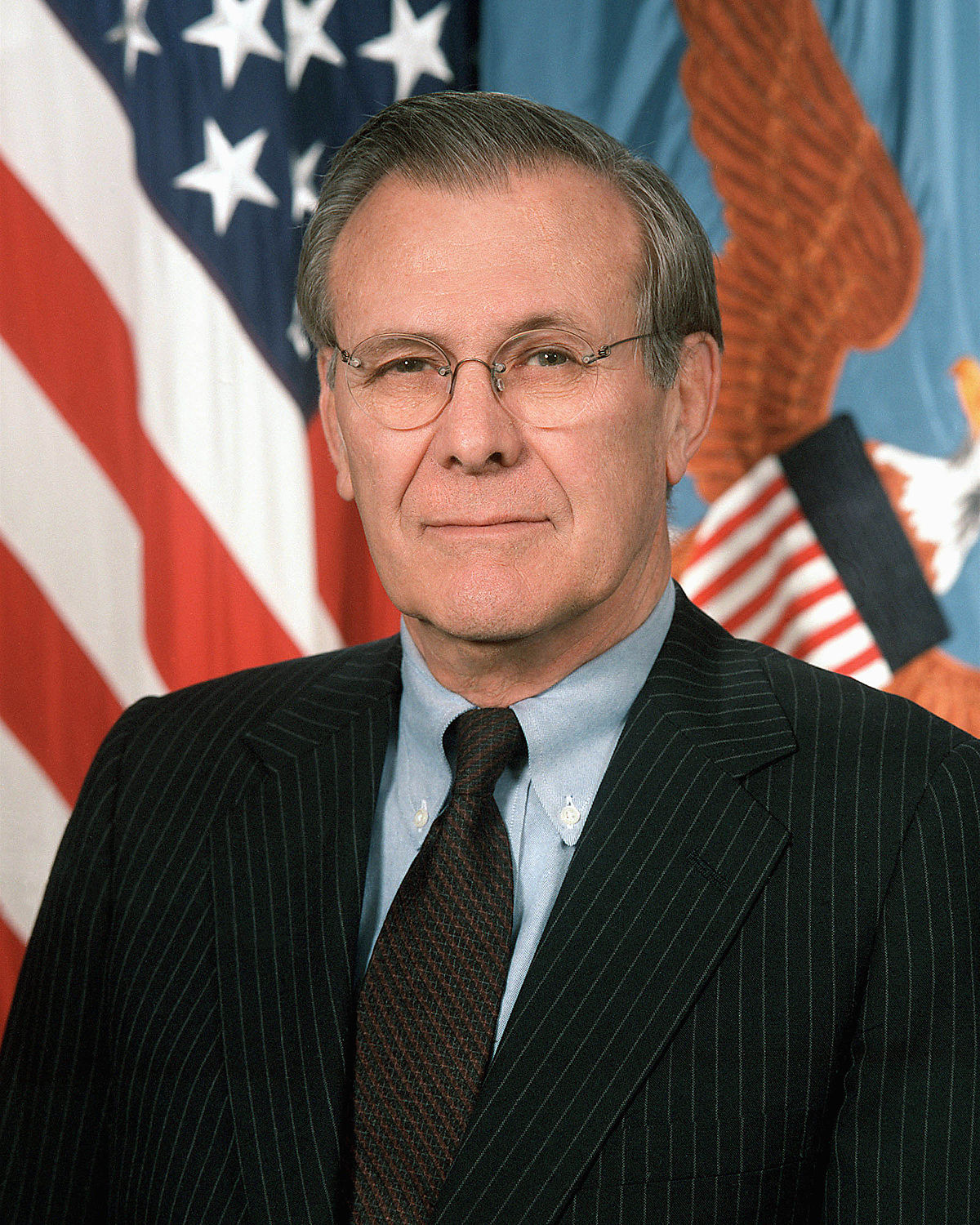

There are known knowns. There are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns. That is to say, we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns, the ones we do not know we do not know. – Donald Rumsfeld

What we really care about is data we haven’t seen yet, mostly data from tomorrow. But what if the world changes, as it always does? If it doesn’t change much, maybe we are OK. If it changes a lot, then what good will our model be? In general, the world changes some. That means that our forecasts are more uncertain that a naive use of our model might suggest.

In Temperance, the key distinction is between the true posterior distribution — what we will call “Preceptor’s Posterior” — and the estimated posterior distribution. Recall our discussion from Section 1.1. Imagine that every assumption we made in Wisdom and Justice were correct, that we correctly understand every aspect of how the world works. We still would not know the unknown value we are trying to estimate — recall the Fundamental Problem of Causal Inference — but the posterior we created would be perfect. That is Preceptor’s Posterior. Sadly, even if our estimated posterior is, very close to Preceptor’s Posterior, we can never be sure of that fact, because we can never know the truth, never be certain that all the assumptions we made are correct.

Even worse, we must always worry that our estimated posterior, despite all the work we put into creating it, is far from the truth. We, therefore, must be cautious in our use of that posterior, humble in our claims about its accuracy. Using our posterior, despite its faults, is better than not using it. Yet it is, at best, a distorted map of reality, a glass through which we must look darkly. Use your posteriors with humility.